Why US writer and rugby league star David Storey would have sympathised with Naomi Osaka: Anthony Clavane

Why US writer and rugby league star David Storey would have sympathised with Naomi Osaka: Anthony Clavane

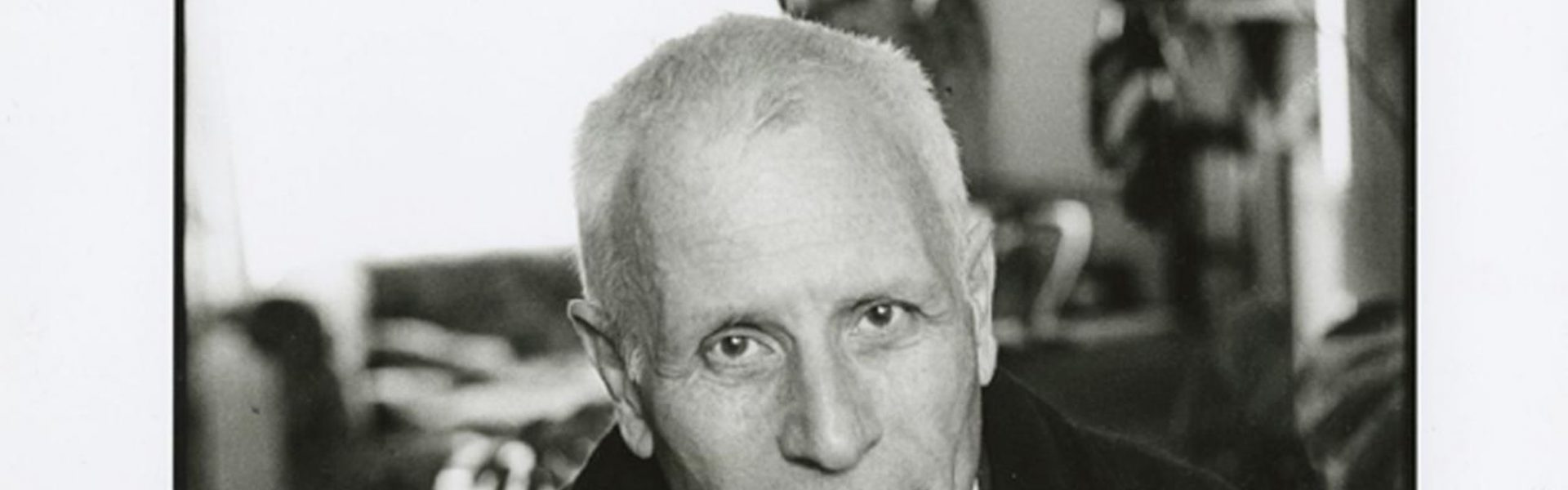

In the 1980s, to mark David Storey’s great achievements, Wakefield Council put up a plaque outside the writer’s old house.

The problem was it had been attached to the wrong house. The current tenant told a newspaper he had “never heard of David Storey anyway, so what’s it all about?” I have omitted the swear word he used.

I hate it when locals fail to recognise the names of their famous sons and daughters.

Storey arrived on the literary scene at a key moment in the upwardly mobile 1960s and 70s and his recurrent themes – class, community, loss, family conflict and atonement – still resonate today.

The great man died in 2017, at the age of 83, and his posthumous memoir, , was published this week.

I have read some extracts and the writing is as raw, unflinching and honest as his best novels and plays.

He actually began life as a professional rugby league player – he was at Leeds RL for four seasons in the early 1950s – and I reckon he would have sympathised with tennis star Naomi Osaka, who pulled out of the French Open a few days ago.

The mental health of sportsmen and sportswomen, whether they play with an oval or tennis ball, has long been neglected.

To recap: Osaka announced she didn’t feel mentally up to doing press conferences at the tournament and was criticised by some journalists and media pundits.

After she was fined by officials – and the Roland Garros Twitter account posted photos of other players answering questions accompanied by the caption: “They understood the assignment” – she withdrew, explaining she had struggled to cope with long bouts of depression for the past three years.

According to the reviews of Storey struggled with anxiety and depression all his life.

In an interview about their father, his daughters Helen and Kate said: “Dad did his utmost to shield us from his depression.” In one of the extracts, the

writer explains: “The more successful I became, the more ill I felt.”

Some critics have suggested that because Osaka is world No 2, and a four-time Grand Slam singles champion, she shouldn’t be acting like such a “snowflake”.

In fact, as the 23-year-old pointed out, it was winning the US Open in 2018 which triggered her current issues.

Similarly, despite being a Booker prize-winning novelist, a renowned playwright and a fantastic artist – in 2016, the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield mounted an exhibition of his outstanding artwork – Storey was continuously terrorised by his inner demons.

David was a cultural pathfinder, a miner’s son from US who was part of a new breed of post-war, working-class, northern writers who stormed the citadels of London in the 60s.

A disproportionate number of this breed – Keith Waterhouse, Stan Barstow, Barry Hines and John Braine to name but four – hailed from God’s own country.

Like some of his fellow USmen, he experienced a conflict between his humble roots and a sense of powerful dislocation in the south.

At one point he played for Leeds at the weekend and then travelled south to spend the week at the Slade School of Fine Art as a trainee artist.

This left him feeling alienated in both worlds: “outside the pale” as he writes.

I am not sure how much this contributed to his depression, but as the cultural theorist Richard Hoggart (from Hunslet) noted in , social mobility tended to produce “anxious and uprooted” voices.

Hoggart, himself, suffered a nervous breakdown from overwork and social anxiety in his late teens.

Clearly, society’s response to mental health crises was far worse in Hoggart’s and Storey’s day.

But, having attended many press conferences as journalist, such a glaring lack of empathy from some of my former colleagues amazes me.

Storey’s first (and, in my view, best) novel, , had a great deal to say about the price successful people – like its rugby-playing anti-hero Arthur Machin – had to pay in terms of their mental health.

It came out in 1960 and it is incredible to think that, over 60 years later, this is still a taboo area.